After reading more about the performance culture that has been developed over recent years by the management, coaching and playing personnel at the New Zealand All Blacks, I wanted to learn more about the environment that has been created at cycling’s Team Sky.

As with Graham Henry’s influence that instigated the cultural shift at the All Blacks, the reputation that Team Sky have developed in the sports performance world has been driven by a key visionary, in this case Sir Dave Brailsford. Brailsford’s drive to transform the sport of cycling in the UK started out at the national governing body, British Cycling and the DNA has been translated to Team Sky as the next stage of his vision.

After setting the fledgling professional outfit a target of winning the Tour de France within 5 years of incorporation, Brailsford led the team, headed by Sir Bradley Wiggins to triumph after just 2 years. Since then, they have repeated the feat 3 more times, with Chris Froome earning the overall yellow jersey once again this year.

In his book, Inside Team Sky, David Walsh gives an embedded commentary of the team’s 2013 assault on Le Tour and whilst the description of the race is fascinating, in this blog, I will concentrate on the key elements of leadership, team culture, environment and attention to detail and how each contributes to the overall delivery of high performance in a sports setting.

LEADERSHIP

The logical place to start is with the leadership that underpins the other elements and is integral to the establishment of the sustained pattern of success.

From the first time I saw Sir David Brailsford speak, it was obvious that this was a man who wore his ambition and passion on his sleeve. There is no doubt that no matter the obstacles that may be thrown in the way, Brailsford demonstrates a steely determination that enables him to roll with the punches and keep on in pursuit of the vision. His unwavering belief in the idea that success can be achieved by following a path different to that traditionally followed in cycling and that he is the man that can pioneer that uncharted route, is extremely enabling both for himself and for those that choose to join him on the journey.

From the early pages in the book, it is apparent that the key leadership traits that underpin Brailsford’s role are humility, empathy and a passion for understanding each member of his team. It is these qualities that earn him their immense respect.

Walsh describes a meeting that takes place at the very beginning of the Tour, where Sir David asks to take a photograph of the team. Continuing, he then asks the group to think about what memories that photograph might evoke six months into the future. He suggests they might want to be able to say that “they were the best group of guys I ever worked with…we were good together on that Tour…that there wasn’t another thing we could have done”. Without drama or threat, this engaging action, ensured that each member of the team understood their responsibility to the rest of the group in honouring that expectation.

Following on from the photograph, Brailsford then underlined his role in supporting each of the team and illustrated a fundamental belief in what they are able to achieve. He continued, “I am just the conductor of this orchestra, you are the guys who play the instruments and you were hand picked for this job because you are the best at what you do”.

Such a simple statement can be so powerful, not because of what is said but what is implied. By describing himself as “the conductor of the orchestra”, Brailsford underlined that he will not interfere with the job that each person had been tasked to do, rather support them in doing it and empower them to operate as they see fit. Walsh uses a great analogy, when he says that “the conductor doesn’t whisper advice to the violinist during the recital”.

In my experience, the best leaders I have worked with have taken this approach and in other organisations, where this autonomy has been compromised, my motivation to reach my potential has suffered. As such, I have always allowed staff working under my management the freedom to execute the necessary tasks in the ways they see most appropriate and avoided the temptation to be seen as looking over their shoulders. In the earlier stages of my management career, I would say the challenge was giving enough space, without being seen to be disinterested or absent, however, I realised that communication is the key to achieving this.

Brailsford’s understanding of how to manage people is further illustrated later in the book, as certain challenges are described in turn. After a couple of particularly gruelling days on the bike, culminating in a withdrawal, several key sub-par performances from the team and an injury, it became apparent that expectations weren’t being met, the strategy needed to be revised and morale needed to be lifted in order to bring the team back together. Brailsford acted emphatically, refusing to be falsely optimistic but also calmly enough so as to avoid the creation of fear or tension.

Initially, Brailsford’s course of action was to ascertain the facts, calmly and analytically. Speaking to each rider, in their own place of comfort (i.e. on their bike whilst out for an early morning ride), Sir David listened to each, establishing their concerns and their state of mind but never judging. A team meeting was subsequently called and ensuring that the riders were given a forum of safety to voice their opinions and the authority to be involved in the decisions, the leader took the reality that was confronting the team and reshaped it.

By asking the group ‘what they are going to stop doing; what they are going to start doing and what they are going to continue doing’, Brailsford deferred to the team to take responsibility, whilst facilitating the process to ensure a resolution was found without delay. Riders were given a new status, by being given jobs that they felt capable of achieving, pressure was relieved and whilst recognising that some were not capable of their highest performance standards, each was asked to give the best of their available capacity. It was apparent that by dealing with the issues rationally and with compassion, the morale of the team was instantly restored and doubts were kept in check. There was a clear recognition that there are moments where you can push people and moments where they need unconditional support.

Throughout the majority of Le Tour, Brailsford is portrayed as cutting a modest, upbeat persona, keeping his hand firmly on the rudder but dishing out praise when it is warranted. The group were praised as a unit and individuals were singled out in recognition of their contributions, yet there was never any excessive back slapping and the reminders to stay on point were the consistent conclusion. This style of feedback is reminiscent of accounts I have heard and read of Sir Alex Ferguson’s management style.

During my time working at British Athletics, Dr. Steve Peters hosted a couple of workshops for the support staff. Peters is a clinical psychologist, who first became involved in performance sport through an invitation from Sir David Brailsford. The two have worked together at Team Sky to instil the recognition that psychology has a significant influence on performance.

Peters’ analogy of the ‘chimp within’ explains that we have have two dominant parts of the brain when it comes to decision making. The emotional chimp, who is irrational and reactive and the computer that is rational and considered. If left ignored, the chimp can raise hell in times of pressure and can compete with the computer when it comes to dictating our actions. It is apparent that Brailsford keeps this awareness to the forefront of his mind when making the big decisions, although that doesn’t mean that occasionally his chimp didn’t occasionally win out in this Tour but those situations seemed few and far between. This analogy was one that resonated with me when Peters presented to us and it is one I have sought to be cognisant of over the years. Just as Walsh reports with Brailsford, the chimp does occasionally win out but those episodes are few and far between these days.

Walsh takes the opportunities to set the context of the Tour experience and the resentment towards Team Sky that was never far from the surface both in interactions with cycling fans, the media and adversaries. It was in the face of some of these confrontations that occasionally Brailsford’s patience was seen to be most tested. Errors of judgement in recruiting a team doctor that was later discovered to have been involved in a doping program and a positive test from a newly signed Team Sky cyclist were cannon fodder for those looking to take aim at Brailsford, given the strict ‘no dopers allowed’ hiring policy Team Sky adopted and have come back to haunt the helmsman.

Walsh reports on a couple of conversations that he shared with Brailsford on these matters and what is clear is that he was quick to acknowledge his mistakes, had considered each one and learnt from them; the moral compass that dictated the initial recruitment policy never wavered. Where the processes were shown to be flawed, Brailsford has taken the lessons on board and new systems have been formulated to reduce the chances of similar errors being repeated.

Errors are not a problem, they are a fact of life and whilst he was prepared for the consequences, there was no hint that he would shirk the responsibility and deny accountability. As Matthew Syed writes in his book, “Black Box Thinking”, we need mistakes to learn and improve, without them our progress would be slowed.

It is clear that this leader enjoys the process, maybe more than the result it prepares for and the focus remains on the bigger picture. Not one to get carried away with the small victories, it appears he is not afraid to scrap plans and redraw them if they are likely to yield a better result. As Walsh quotes “if you feel too good about victory, you lesson your chances of repeating it”.

To this end, Brailsford was reported to have put the first week of December aside to review the season and rework the team’s core values, focussing on enhancing the behavioural side of the performance model. By identifying behaviours that might stop the team from succeeding, or might cause disharmony amongst the group and recognising these losing traits, Brailsford was confident he could then find winning ones. Excellence never stands still.

It is this behavioural side, the culture and values that have been facilitated by Brailsford, that are a key component to the sustained level of success.

TEAM CULTURE

As I discussed at length in my recent review of “Legacy”, by James Kerr, culture is king. If the culture isn’t developed to encourage development of self and team, success will be short-lived and sacrifice for the greater group will be overlooked by individuals in favour of more selfish motivators.

When Brailsford first took the reigns at Team Sky, the staff turnover was high during the initial three year period. This was partially due to the expectation of a rigorous work ethic but also in part due to the growth mindset, team focus and innovative approach to performance. As I have found in my own experience of establishing change in sports organisations, not everyone is suited to operating in high performance organisations, as they are very demanding and don’t welcome those people that don’t like to be challenged, preferring instead to remain in a comfort zone.

The culture at Team Sky expects each member of the team to do all in their power to increase the chances of achieving a successful outcome. This involves doing things differently in small ways or in big conspicuous ways but there is an insistence on a willingness to being accountable, responsible and showing a willingness to absorb lessons when the outcome is counter to expectation. It seems from “Inside Team Sky”, that such eagerness to learn from mistakes is enabled because of the supportive character of the group, with people from leadership down asking “how can I help somebody improve?” and sticking together throughout the process. Without integrity and openness, a person joining Team Sky would not be a good fit, as they would not be able to honour these qualities.

Rod Ellingworth, Brailsford’s right hand man, is a perfect example of this supportive nature. Walsh describes Ellingworth’s willingness to roll up his sleeves and help with any task when help is required; a man that is “happy to hew wood or draw water”. A personable, caring, polite, helpful and genuinely concerned man, Ellingworth is seen as the team’s moral and ethical rock, immune to celebrity, or wealth and as such is respected by all in the organisation, as well as those that have moved on to other teams. His emotional intelligence is valued in the relationships he nurtures and his technical capabilities reinforce his reputation as an authority in the sport.

In an interview with Walsh, Brailsford was quick to praise Ellingworth’s ability to operate on three different levels of understanding. Using the analogy of the three hands on a clock, Brailsford explained how Ellingworth can manage elements in the short term (the here and now, today or tomorrow), the medium term (what needs to be happening six weeks from now) and the long term (what needs to be planned and considered that will happen in twelve months) concurrently.

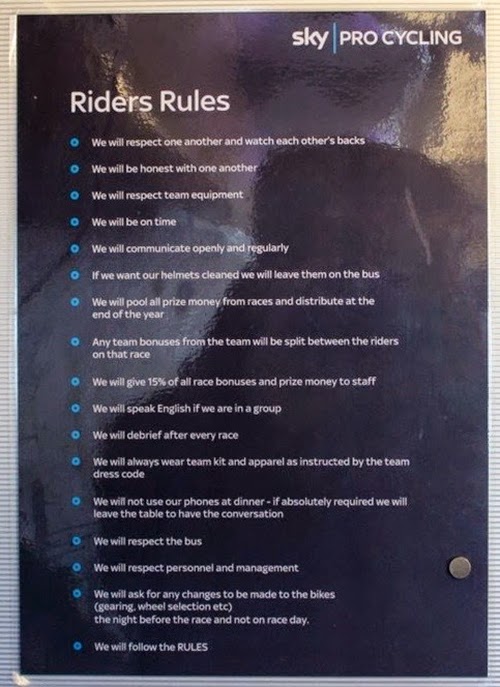

As with any culture that underpins success in a winning organisation, there are non-negotiable standards that have been agreed upon by the members in the group. Walsh describes how Team Sky’s Riders Rules are laid out and posted for all to see on the bus and in team areas. There was no debate, no question, all were involved in writing the rules and all must adhere to them. In my experience, the least effective organisations I have worked in have not cooperatively set the non-negotiable standards to which each person has to adhere and as a result, individuals seeking to serve their own agenda have been granted the leeway to shirk responsibility and accountability.

On the one occasion in Team Sky that the rules weren’t followed, the relationship between two of the team’s star performers, Sir Bradley Wiggins and Chris Froome, was damaged irreparably. Whilst there were other contributing factors to the breakdown, Brailsford himself decided that enough was enough and demanded the rules were followed after the strained relationship threatened the success of the team.

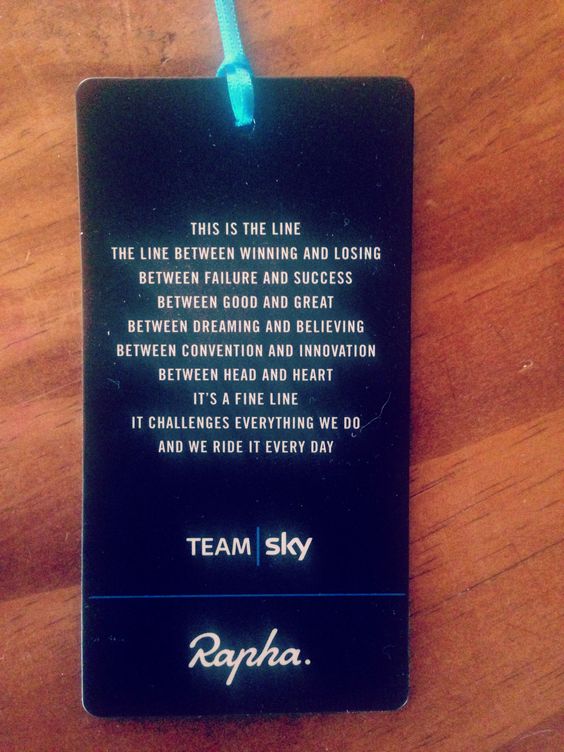

This fine line between succeeding, allied to alignment with the culture and values, and failing, is illustrated in each item of the Team Sky uniform. The predominantly black background is bisected with a thin blue line, which represents the thin line between success and failure. Not only is it apparent on the jerseys of the riders, it is translated on the team issue cell phones, the chef uniforms and the team ID passes.

The relationship between culture and environment is a close one, often with blurred lines of separation but Walsh describes the symbiosis well.

ENVIRONMENT

The environment described by Walsh is one that is well organised, intelligently planned and prepared with meticulous attention to detail. Nothing is overlooked in the effort to ensure that team performance is not compromised from a controllable variable. By working to a carefully formulated plan, Brailsford believes that the likelihood is that the computer, not the chimp will run the race and the controllable variables are indeed controlled.

Walsh recalls a discussion with lead rider, Chris Froome, following a difficult stage where the planned support intended for Froome had been unable to maintain the required pace. Considering his options, Froome took a calculated risk and attacked the peloton, which resulted in a favourable outcome. This lack of emotion and dominance of ‘the computer’ in the decision-making process, was illustrated by Froome’s quote: “when everyone misses the bus, what matters is how you react after it has departed.”

Careful planning also enables objective review and reflection of the outcomes, related to the process and as such this facilitates the learning that can be gained from mistakes that occur. It is in this area that I have seen some medical and athletic training personnel struggle most, particularly in relation to rehabilitation cases, as there has been a preference for day-to-day management rather than taking the time to think through the entire process and map out short, medium and long term plans to guide the process.

Correcting mistakes, however, is one thing but finding a better way forward is another. As such, Team Sky have concentrated innovative resources to identify ways to fail less and succeed better and prefer to ask the question “why not?”, as opposed to “why?”. In the black and blue world of Team Sky, this version of kaizen is called “Marginal Gains”.

ATTENTION TO DETAIL - “MARGINAL GAINS”

Team Sky’s famed attention to detail was inherited from British Cycling and christened the “Marginal Gains” approach, from the philosophy that by identifying 100 things that can be done 1% better, the cumulative advantage will add up to a significant performance gain.

Ideas born from this kaizen approach include riders’ mattresses being transported around the world; setting optimal operating temperatures in the mechanics’ work spaces; making alcohol rub available throughout the team spaces to reduce risk of transmitting infection; adopting the routine of double checking bike modifications and setting up joint ventures with companies outside the sports industry to remain at the cutting edge of technology.

Objective information is collected where possible to guide the process, however, whilst performance data is carefully collected, insightfully analysed and promptly fed back, there is also a recognition of Einstein’s opinion that “not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted”.

Occasionally this close attention to detail has meant that larger mistakes have been made, such as the issues highlighted in the recruitment issues. As Brailsford admitted, in these instances they could have been accused as “worrying more about the peas than the steaks”. However, such inquisitive and innovative philosophies are crucial in building an environment that can support a high performance culture.

Reading Walsh’s account of Team Sky’s world was a really valuable insight into one of the most revered high performance organisations in world sport. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many of the leadership and cultural traits that are described in his account corroborate with texts that describe those in other high performing sports teams that have enjoyed sustained success, such as the All Blacks, Sir Alex Ferguson’s Manchester United and the San Antonio Spurs. As such, cross referencing such details with other theoretical commentaries has helped me reflect on my practices and identify how I would approach challenges differently in the future.